What is acquired hypothalamic obesity?

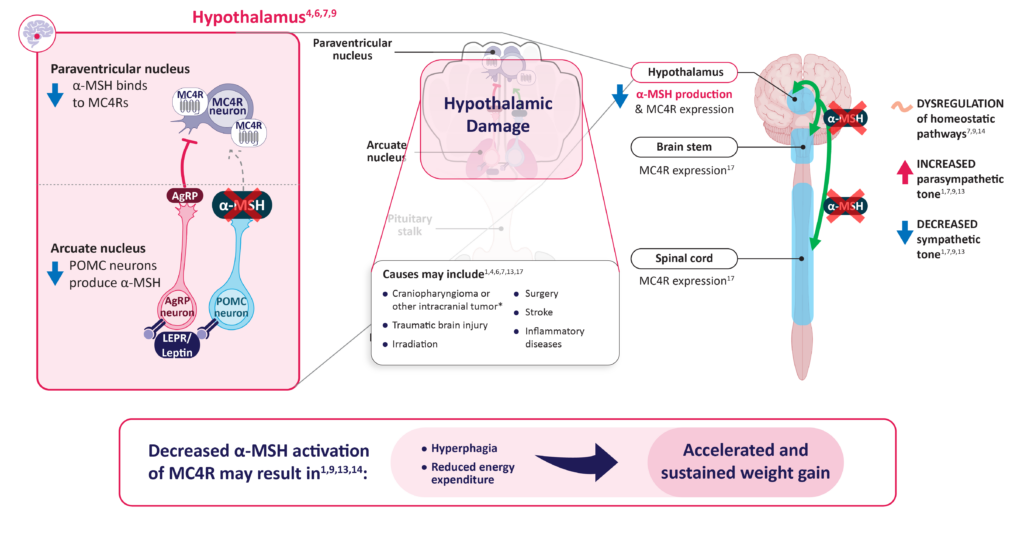

Hypothalamic injury may lead to decreased alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) production and impairment of MC4R pathway signaling. Patients with acquired hypothalamic obesity experience accelerated and sustained weight gain, often accompanied by hyperphagia (a chronic pathological condition characterized by insatiable hunger, impaired satiety, and persistent abnormal food-seeking behaviors) and/or decreased energy expenditure.1,5-14

Acquired hypothalamic obesity can occur as early as 6 months following hypothalamic injury, in childhood or adulthood.5,9,15,16

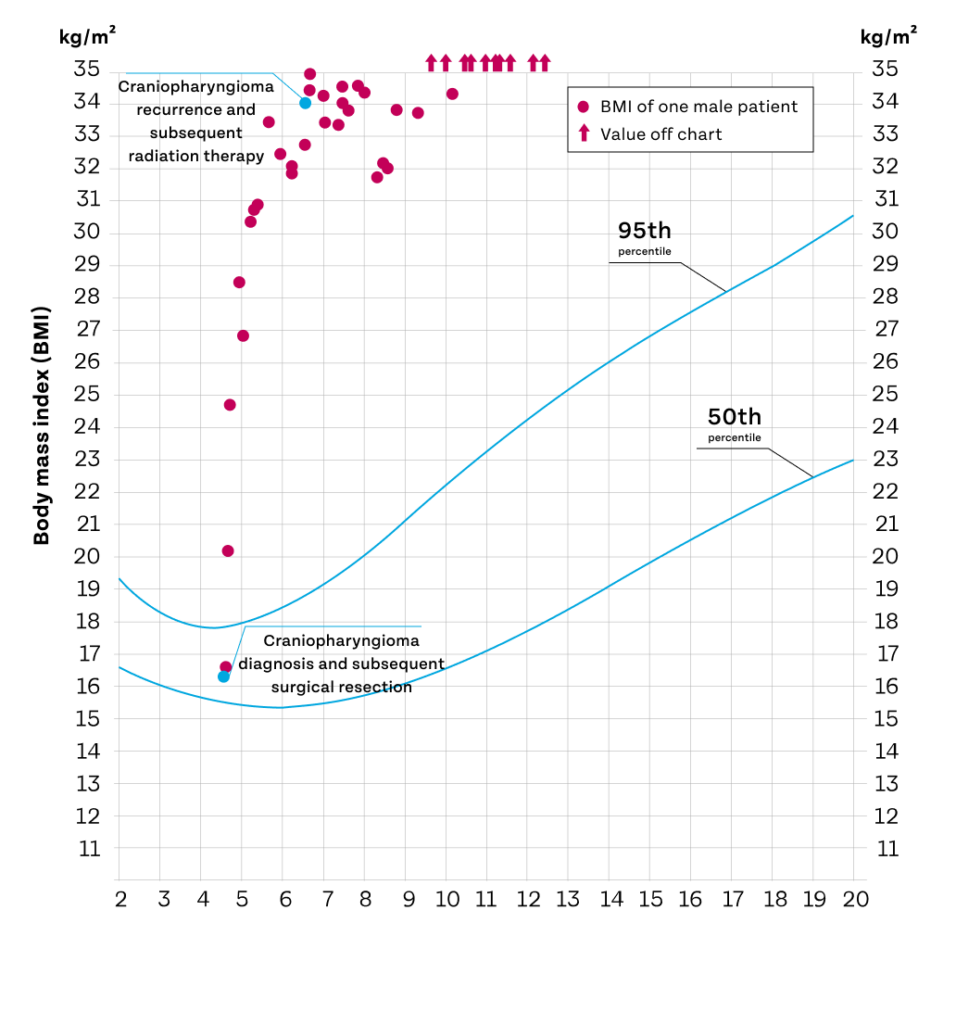

Growth chart of a male patient with acquired hypothalamic obesity following craniopharyngioma and subsequent surgery1

Lines represent BMI-for-age percentiles for boys, 2–20 years.

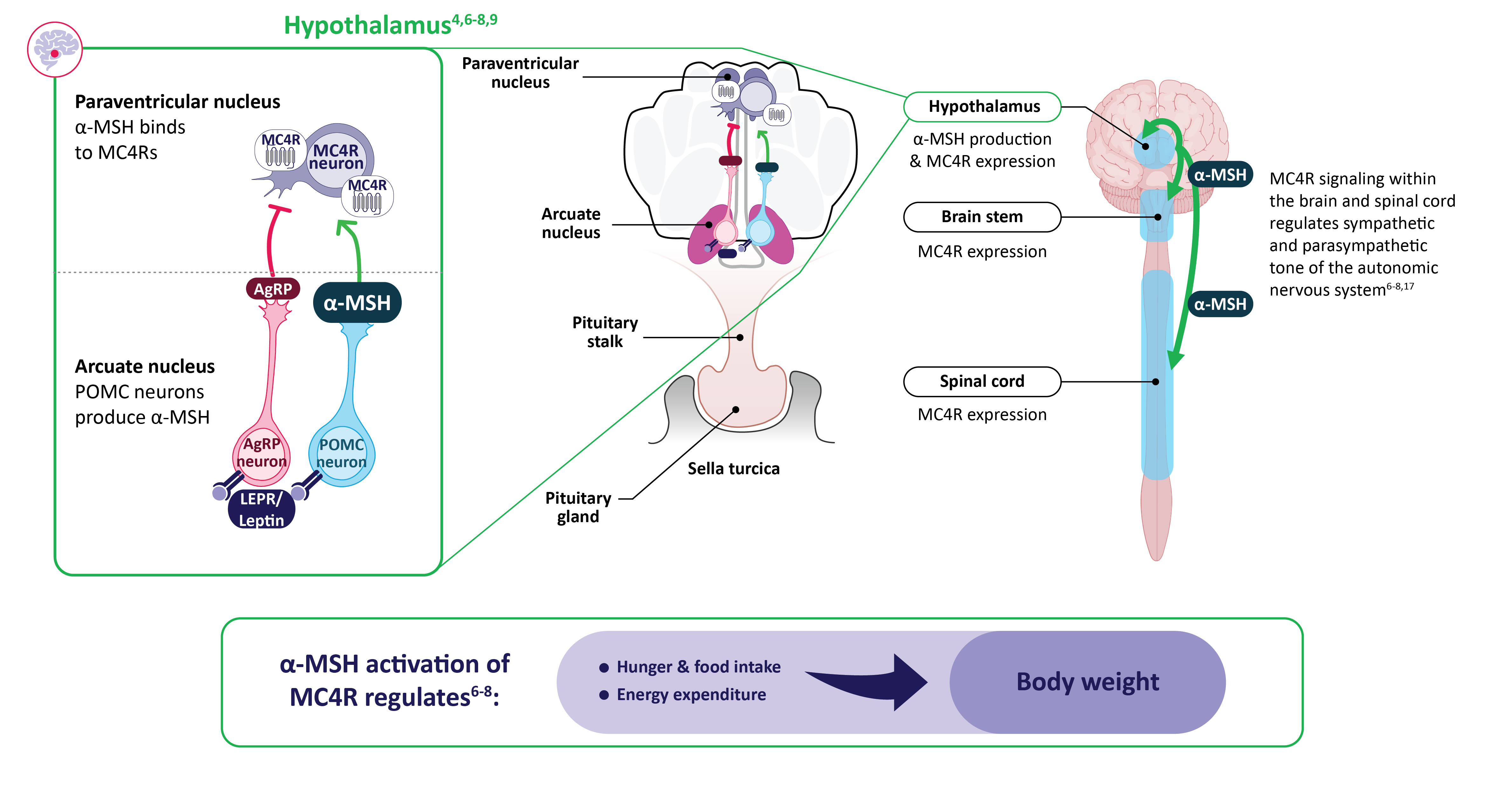

Melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) pathway impairment in acquired hypothalamic obesity

- α-MSH, a key neuropeptide naturally produced in the hypothalamus, activates MC4 receptors in multiple locations, including the hypothalamus, brain stem, and spinal cord, to drive MC4R pathway signaling4,6-9

- Hypothalamic injury may decrease α-MSH production, which impairs MC4 receptor pathway signaling, and can result in accelerated and sustained weight gain due to decreased energy expenditure, increased energy intake, and/or hyperphagia1,10,13,14

α-MSH ACTIVATES MC4R pathway signaling to regulate energy balance and body weight6-8

α-MSH, alpha–melanocyte-stimulating hormone; AgRP, agouti-related peptide; LEPR, leptin receptor; MC4R, melanocortin-4 receptor; POMC, proopiomelanocortin.

Decreased α-MSH production due to hypothalamic injury may impair MC4R pathway signaling and lead to acquired hypothalamic obesity1,13,14

α-MSH, alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone; AgRP, agouti-related peptide; LEPR, leptin receptor; MC4R, melanocortin-4 receptor; POMC, proopiomelanocortin.

Early recognition of clinical characteristics associated with hypothalamic injury is a critical step in identifying acquired hypothalamic obesity

Indicators that may help distinguish acquired hypothalamic obesity from other forms of obesity can include:

- Hypothalamic injury followed by accelerated and sustained weight gain7,19

- Recognition of an accelerated increase in weight following injury to the hypothalamus can indicate acquired hypothalamic obesity5,7,10

- Presence of 1+ hypothalamic/pituitary hormone deficits due to hypothalamic dysfunction10

Clinical characteristics of acquired hypothalamic obesity

Hyperphagia11,12,20

- A chronic pathological condition characterized by insatiable hunger, impaired satiety, and persistent abnormal food-seeking behaviors

- Increased hunger or hyperphagia has been reported in approximately 70% of individuals with acquired hypothalamic obesity

Reduced energy expenditure21-26

- Reduced energy expenditure is commonly seen in patients with acquired hypothalamic obesity and likely contributes to the development of obesity, even in the absence of increased food intake

Accelerated and sustained weight gain7,9,10,19

- Weight gain can be observable years prior to a diagnosis of acquired hypothalamic obesity

- For example, a person may present without clinical obesity but experience a sudden accelerated increase in weight following an injury, which can suggest acquired hypothalamic obesity

- Decreased physical activity

- Increased fatigue

- Sleep disturbances

- Deficiencies in pituitary hormones

- Hyperinsulinemia

- Behavioral disturbances

Acquired hypothalamic obesity represents a significant long-term burden for patients and caregivers

- Acquired hypothalamic obesity is severe, progressive, and associated with morbidity and intractable burden that significantly decreases quality of life10

- Patients with acquired hypothalamic obesity and their caregivers have reported unrelenting hunger, drastically reduced energy levels or physical activity, disrupted sleeping patterns, and substantial weight gain following hypothalamic damage, which was associated with negative impacts on self-esteem, emotions, and family dynamics30

- Rapid onset of weight gain has been associated with increased risk of obesity-related morbidity and mortality16

- Patients with acquired hypothalamic obesity can develop long-term health complications, including metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD; previously known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD), dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)27,28

Managing acquired hypothalamic obesity can be challenging for patients and healthcare providers

- Early recognition of clinical symptoms (eg, hyperphagia, accelerated and sustained weight gain) after hypothalamic injury is a critical step in diagnosing and proactively managing the disease, which may help slow the progression of weight gain31

- Diagnosis may be confounded by temporary weight gain from medications or hormone replacements7

- There is a lack of clear treatment algorithms for acquired hypothalamic obesity31

- Possibly because of its unique pathophysiology—with involvement of the MC4R pathway—compared with general obesity, conventional pharmacologic approaches have shown limited to no sustained benefit in patients with acquired hypothalamic obesity. There are currently no FDA-approved treatments specifically indicated for acquired hypothalamic obesity3,7,31

- Multiple clinical trials are ongoing to further evaluate pharmacological approaches in acquired hypothalamic obesity5

Learn more

For more information about acquired hypothalamic obesity, visit hcp.differentobesity.com or find more resources at hcp.rhythmtx.com/resources.

Explore the MC4R pathway

Strengthen your understanding of the MC4R pathway.

Understand rare genetic MC4R pathway diseases

Expand your knowledge of rare genetic MC4R pathway diseases.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; MAFLD, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; MC4R, melanocortin-4 receptor

References